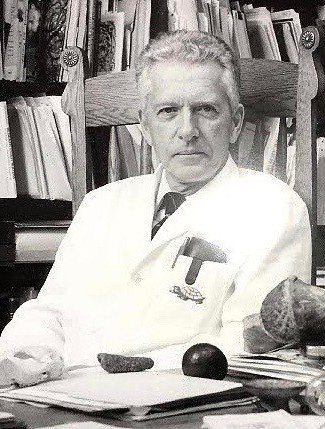

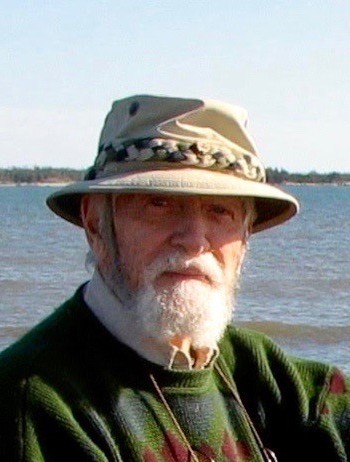

Obituary of John "Sherman" Bleakney

The only child of Ruby Isadore Mitchell of Seattle, Washington, and Guy Garfield Bleakney of Wolfville, Nova Scotia, John Sherman Bleakney was born in Corning, New York. He grew up in Boston, where his father was a Baptist minister, but summers were spent at his father’s home in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. From an early age, Sherman loved the outdoors and both his parents encouraged his interest, his father mentoring him in hunting and woodsman skills, and his mother in the scientific study of the natural world. The family moved back to Wolfville before Sherman entered high school, and by the time he became a freshman biology major at Acadia University in Wolfville, his room was filled with zoology and botany books and specimens of what he had collected.

He developed an early interest in herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians. Story has it that to first get the attention of his future wife, Nancy Tyler, a fellow biology student at Acadia, he put a frog down her lab coat. He went on to do his PhD at McGill University on the distribution of reptiles and amphibians in eastern Canada. He and Nancy spent their honeymoon camping through Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes, collecting and documenting frogs and turtles and snakes along the way, culminating in the book, “A Zoogeographical Study of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Eastern Canada”. Sherman took the position of Curator of Herpetology at the National Museum in Ottawa in the early 1950s, eventually earning the epithet of one of the “fathers of Canadian herpetology” for scientifically legitimizing this previously neglected field. In Ottawa, his and Nancy’s children, Jill and Peter, were born. Then In 1957, a biology professorship opened up at his alma mater, and Sherman and his family returned to Wolfville.

At Acadia University, he lectured undergraduates in comparative vertebrate anatomy and invertebrate zoology, supervised graduate students, wrote over 80 scientific papers in 23 journals, and participated enthusiastically in the Biology Department and Acadia life for over 35 years. As a diligent researcher and creative thinker who was not afraid to stretch academic boundaries, always with a healthy dose of humour and irreverence, he leaves a legacy of scientific research and publications on everything from leatherback sea turtles to sea slugs to chimpanzee art to the origins of European medieval mollusc symbols to Acadian dykeland construction methods.

Sherman may best be remembered for his research on sea turtles. In the 1960s, he established relationships with local fishermen to research the leatherback sea turtles they were finding off Nova Scotia. Jill and Peter remember their father dissecting a leatherback in the back garden, as it was too large for the Acadia lab tables. (Nancy’s beautiful English perennial garden that she had created in our Wolfville backyard had a vaguely oily fishy smell for years afterwards, much to her chagrin.) He established the surprising fact that these huge marine reptiles ate mainly jellyfish, and that they were regular visitors up the eastern coast of Canada. Years later, his sea turtle legacy earned him the honour of having the first satellite-tagged leatherback, Sherman, named after him. He then moved from herpetology into marine invertebrate zoology, focusing on the Minus Basin. With Joan Bromley, he wrote the Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the Minas Basin, published by the National Research Council. The discovery of a sea slug on the Minas Basin mudflats peaked his research interest, and he morphed into a marine invertebrate zoologist specializing in nudibranchs, i.e. sea slugs. This research took the family for a year to the U.K. and Europe in the 1960s, where Sherman worked in marine labs in England, France and Scandinavia. Several years later, he and Nancy followed the sea slug trail all around the Pacific rim, working in Japan, Hong Kong, Australia and Hawaii. All told, he discovered several new species of these beautiful but little-known molluscs, developed new techniques for collecting them and photographing their striking colours, and pioneered the use of the scanning electron microscope to document their delicate structures. His enthusiasm for his subject spills over in the surprisingly readable, and even humorous, “Sea Slugs of Atlantic Canada and the Gulf of Maine” (Nimbus 2004).

Over the years, Sherman mentored and supervised many honours and graduate students at Acadia University, and his students have gone on to careers at various national parks and research institutes, universities all over North America, the Canadian Museum of Nature, the Royal Ontario Museum, and the Smithsonian. Among his greatest pleasures in later years was meeting and hearing from these students, some also now retired themselves, about their work and the knowledge and enthusiasm from their time at Acadia that they carried into their careers. His iconoclastic and humour-laden undergraduate lectures were legendary, and in 1987 he was awarded the Acadia Alumni Award for Excellence in Teaching for what his students described as “a rare amalgam of superb teaching, innovative research, charisma and general caring about students.”

Sherman was devoted to his family and kids. When not at Acadia, he was home doing things like digging a homemade backyard swimming pool, painstakingly sawing out wooden jig-saw puzzles, taking us on nature hikes and canoe trips, and doing much of the work building a cabin on the ocean at Chester Basin. He and Nancy planned lengthy family trips to make the most of Dad’s conferences and research trips, including camping across North America (via station wagon and tent) and through Europe (via tiny Dormobile pop-up roof camper van with English left-hand manual drive, which Sherman drove accident-free in Europe on the “wrong” side), and two canal boat trips through England – all in the days of corresponding by snail mail to book lodging and travel arrangements, a formidable undertaking in itself.

Sherman was an avid scuba diver. He was a founding member of the Acadia Scuba Diving Club and, with Erik Hansen and his Scuba Club colleagues, first mapped the 18th century underwater shipwreck battleground off Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, which eventually led to the establishment of the Louisbourg National Historic Site. Through the Greenwood Airforce Base, he accompanied Canadian Airforce rescue divers to the Caribbean to document coral reefs there. To impart to us kids his enthusiasm for the ocean and diving, he painstakingly made us child-size wetsuits (these were the days before kids’ wetsuits were sold in Canadian Tire!), using sheets of thick neoprene rubber and rubber glue (the smell of which permeated our house when he was working on them, taking out a few of our brain cells, no doubt), measuring us up, cutting the pieces from the rubber sheets, and expanding the suits by gluing in strips of rubber each year as we grew. The snorkeling trips with dad off the shores of Nova Scotia were a highlight of our childhood, swimming through schools of ink-squirting squid, over fields of sand dollars, and even thrilling nighttime expeditions through glowing diatomaceous bioluminescence where the ocean left trails of light all around us.

Even though Sherman was first and foremost a scientist and boots-in-mud naturalist, he was also very encouraging of his son Peter’s two non-biological passions - cars and music. Maybe when Sherman purchased a 1968 Austin Mini for 15-year-old Peter to tinker with, he was anticipating Peter’s career as an automotive journalist; and when he later co-signed a bank loan that enabled Peter and his band, Pyramid, to purchase a van and a big PA system, all in the pursuit of rock ’n’ roll fame, maybe he foresaw that Peter would also became a professional musician. And even when Jill veered away from biology to pursue anthropology and then medicine, his support was unwavering, although it probably helped that she did marry a man with a snake tattoo!

Skip forward a decade or two, and Sherman and Nancy had 5 grandchildren. From their visits back to Nova Scotia, the grandkids have memories of him building a big painted school bus for them out of appliance boxes, making a kid-size tinman outfit to dress up in after they and Grampy had watched the Wizard of Oz, devising an elaborate treasure hunt for pirate gold on a Nova Scotia beach (maybe a little too realistic!), laughing uproariously at Grampy’s magic tricks, and wading in tide pools to collect sea life that they then marvelled at through Grampy’s very cool dissecting microscope. Grampy Sherman remained a kid at heart and a great jokester throughout his life, and his grandkids brought out the best of this in him.

After retiring from Acadia, Sherman and Nancy made a chance observation of an ancient wooden sluice gate sticking out of the Minas Basin mud near Wolfville. That led to Sherman’s 15-year retirement project of applying a biologist’s eye to the archaeological, historical, geographical, and cultural knowledge surrounding the construction of the French Acadian dykelands around Wolfville and the Minas Basin. Sherman was able to literally deconstruct the Acadian’s 18th century dyke-building process, and published a book about it (Sods, Soils and Spades, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004). His research and presentations helped contribute to Grand Pre being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012, and a permanent exhibit of the dyke-building techniques he brought to light is in the entrance hall of Grand Pre-National Historic Park.

Sadly, after 45 years of marriage, Nancy passed away, with Sherman at her side. He was devastated. But in characteristic form, within a year or two he was traveling again to places of historical and zoological interest. On a Royal Ontario Museum tour in Egypt, he met the second love of his life, Elizabeth Walter of Toronto. For the next 15 years, Sherman and Elizabeth travelled on four continents, documenting their travels in beautiful photographs and Elizabeth’s sketches and paintings. With Elizabeth, he rekindled his love of the North (where he had done wildlife research as a student and later travelled with Nancy), and revisited N.W.T, the Yukon and Nunavut, deeply unsettled by the starkly obvious effects of climate change as compared to his previous visits a few decades earlier. He also started to revisit his earlier theories of the centrality of animal bones and anatomy to human religious beliefs and art, but he ran out of time to get these thoughts into publishable form.

Sherman’s motto throughout life was “always anticipate”. Things had to be planned in advance and well done. If something was not done properly or needed fixing, Sherman was there to do it, and he did not suffer people who procrastinated or did a sloppy job. So, when Sherman could no longer read his Scientific American or Blomidon Naturalists Society newsletter, could no longer walk the shores of his beloved Minas Basin, and, as he said, he had contributed all he could to our understanding of this amazing planet, he chose to avail himself of Medical Assistance in Dying in anticipation of his demise. His final musings to us, Jill and Peter, were on the similarity between the sea turtle flipper bones, mounted on his study wall, and his own human hands, and he said he wished he could write just one more paper, on how human, sea turtle, bat and elephant “hands” all have nearly identical bones, and if there was only a way of intellectually grasping the awesome mystery of the molecular/genetic/cellular/epigenetic/evolutionary processes that shape our human and animal hands so differently and yet so much the same ….

Sherman passed away peacefully at home in Wolfville on October 25, 2019 at the age of 91. He is predeceased by his wife Nancy Patricia (Tyler), his life partner and best friend. He is survived by his loving children, daughter Jill Blakeney (Dwight Sayers) and son Peter Bleakney (Claire Toth), and his grandchildren, Angela, Christopher, Evan, Alex and Lee, as well as his later-in-life partner, Elizabeth Walter. As per his wishes, Sherman’s ashes were scattered on the ebb tide into his beloved Minas Basin, merging with the world’s highest tides, out into the Bay of Fundy to the Atlantic. Truly a life well lived.

Our family would like to thank the staff of Wickwire Place in Wolfville for their support of Sherman, his family doctor Dr. Hazen Burton and nurse practitioner Erica Maynard for their care, and the staff of Serenity Funeral Home.

In lieu of flowers, memorial donations may be made to the Canadian Sea Turtle Network. Arrangements have been entrusted to Serenity Funeral Home, 34 Coldbrook Village Park Dr., Coldbrook, NS, B4P 1B9 (902-679-2822).

SERENITY

FUNERAL HOME

Serenity Funeral Home and Chapels

Monday to Friday 8:30 - 4:30

24/7 By Phone

198 Coldbrook Village Park Drive, Coldbrook

N.S. B4R 1B9

Phone: (902) 679-2822

Fax: (902) 679-0424

NEW ROSS FUNERAL CHAPEL

New Ross Funeral Chapel:

By Appointment Only

4935 Hwy12,

New Ross, B0J 2M0

Mailing Address:

198 Coldbrook Village Park Drive, Coldbrook

N.S. B4R 1B9

Phone: (902) 689-2961

Fax: (902) 679-0424

DIGBY COUNTY FUNERAL CHAPEL

↵

Digby County Funeral Chapel

By Appointment Only

367 Highway 303,

Digby, B0V 1A0

Mailing Address:

198 Coldbrook Village Park Drive, Coldbrook

N.S. B4R 1B9

Phone: (902) 245-2444

Fax: (902) 679-0424